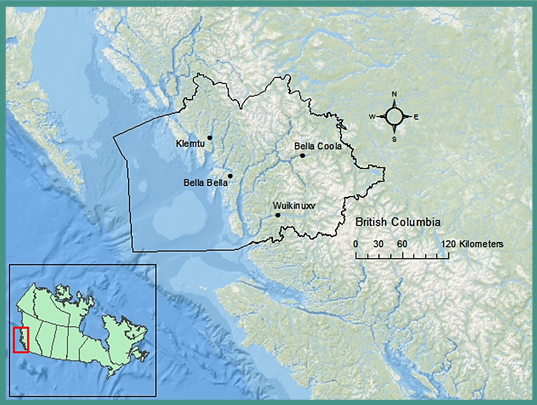

As I’ve moved deeper into exploring digital literacy challenges in Indigenous communities, I decided to focus specifically on the Nuxalk Nation in the Bella Coola Valley of British Columbia. This community, like many others in remote parts of the province, faces systemic barriers in accessing and leveraging digital technologies for education, cultural preservation, and community development.

My learning journey began with broad research on Indigenous digital equity, but has now narrowed to understanding how geography, infrastructure, and colonial legacies intersect to create the modern digital divide.

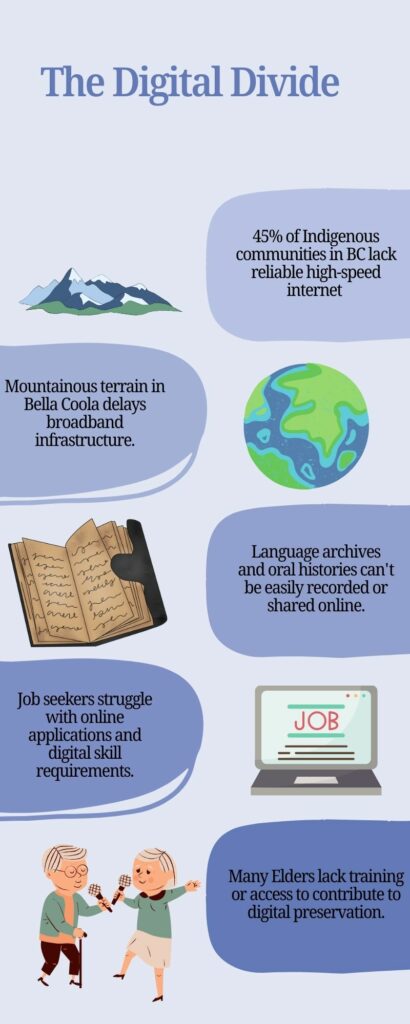

A major “aha” moment came while exploring the First Nations Technology Council (2020) report. It emphasized that internet access is not just technical infrastructure—it’s a pathway to autonomy, education, and economic participation. When the Nuxalk community lacks high-speed connectivity, they are also deprived of chances to engage with online language revitalization tools, digital storytelling, or e-commerce opportunities.

In exploring community-based examples, I came across local education initiatives that try to overcome these barriers, including the integration of Nuxalk language content into offline learning materials. These hybrid approaches demonstrate the innovation communities are using when digital infrastructure falls short. I found this inspiring, it shows resilience and a commitment to keeping culture alive, even without full digital access. Yet, it also highlights that Indigenous communities are often forced to adapt around systemic failures, rather than being supported through proactive digital inclusion policies.

Another layer I discovered in my learning is how digital literacy also intersects with digital sovereignty. Indigenous data governance is a growing field that emphasizes the right of Indigenous communities to control their own digital narratives and the storage and use of their data. This made me reflect on how digital literacy should include not just how to use tools, but how to own and govern digital spaces. For the Nuxalk and other nations, this means building culturally aligned platforms and ensuring community control over digital heritage.

Key Takeaways:

- The digital divide is a form of modern colonization, limiting the sovereignty of Indigenous communities over their knowledge and future.

- Social isolation due to poor connectivity restricts participation in national and global conversations.

- Economic disadvantages are amplified when communities can’t access digital tools for employment, education, or entrepreneurship.

- Local leadership and community-based solutions are essential—top-down approaches often fail to understand the specific cultural, geographic, and historical contexts of Indigenous communities.

- Digital literacy must be developed in a way that respects Indigenous pedagogies and worldviews, not just Western technological norms.

- Digital sovereignty should be included in digital literacy education, emphasizing Indigenous control over data and digital heritage.

Resources:

First Nations Technology Council. (2020). Report on Indigenous Digital Equity in British Columbia. https://technologycouncil.ca

UVic Human Resources. (2025). Ergonomic tips for working at home [PDF]. University of Victoria. https://www.uvic.ca/hr/assets/docs/ergonomics/ergonomic-tips-working-at-home.pdf

https://www.nuxalk.net/html/maps.htm