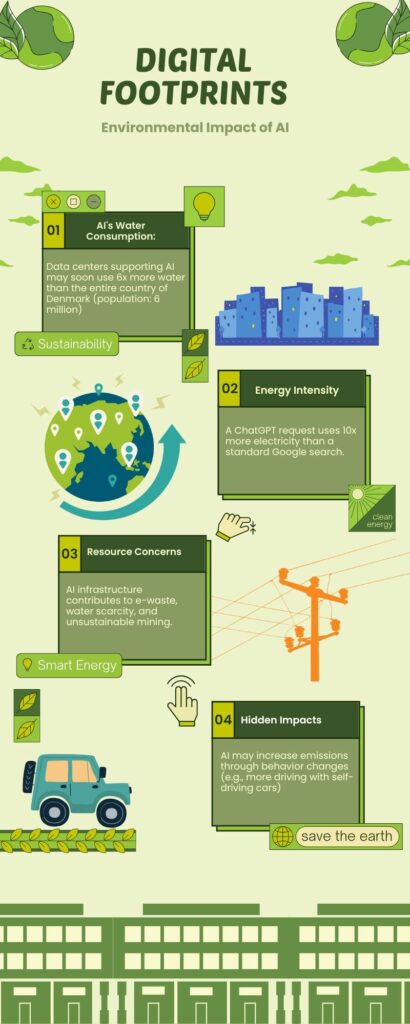

Throughout this exploration into digital literacy and Indigenous sovereignty, I’ve come to understand that technology is more than a utility it is a cultural bridge, a protector of knowledge, and a vessel for resilience. Digital literacy for Indigenous communities, particularly across British Columbia, is not just about technical proficiency; it is about access, voice, and self-determination. It’s about creating, not just consuming owning data, not just storing it and ensuring that technologies reflect Indigenous ways of knowing rather than colonial structures. I began this journey looking at digital access gaps, but what I discovered was much more layered. The issue is deeply tied to historical dispossession, colonial policies, and infrastructure inequities that persist today.

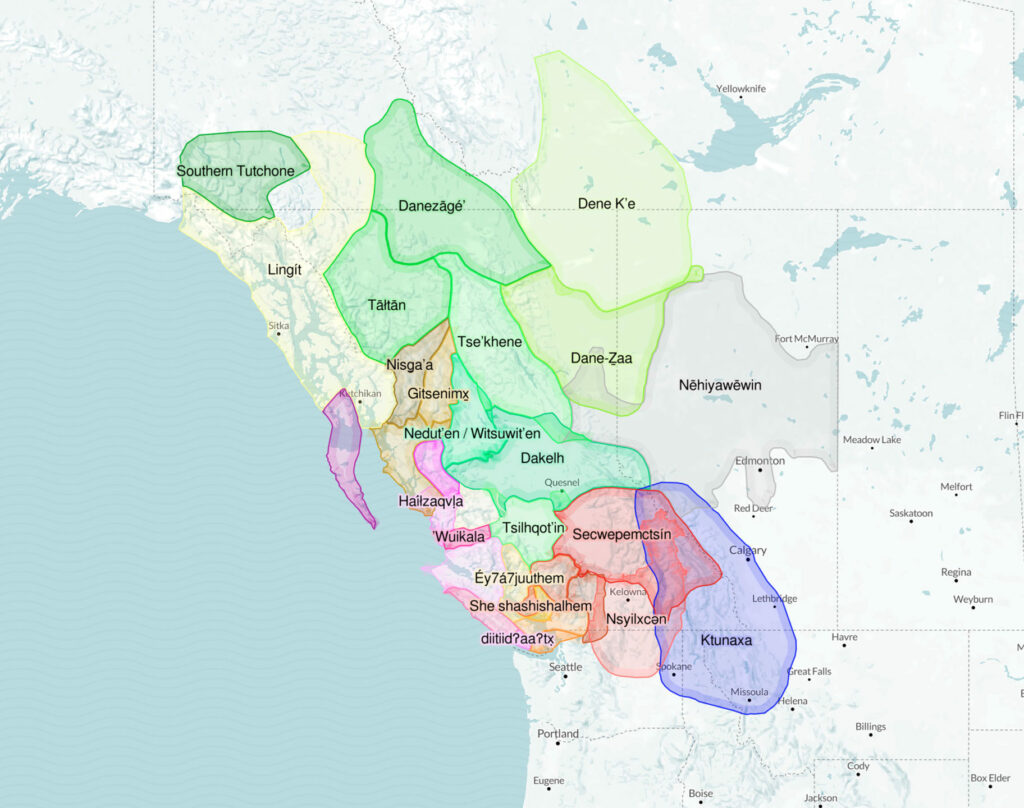

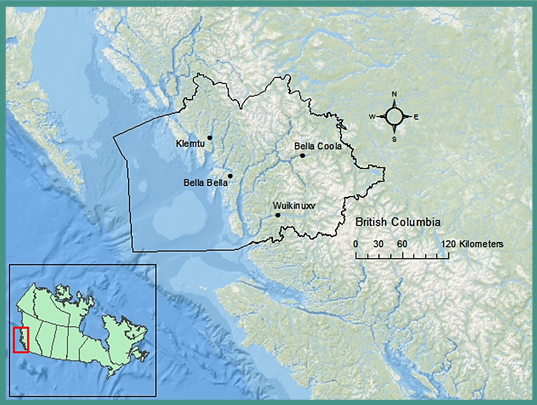

The First Peoples’ Map of B.C. became a powerful turning point in my learning. It showcases Indigenous languages, arts, and culture through an interactive, community-led platform. Far from being a static database, it is alive with Indigenous presence, highlighting 36 languages, artist profiles, and traditional territories. What’s crucial is that it is run by Indigenous people for Indigenous people. This is digital sovereignty in action: communities controlling their own narratives, maintaining guardianship over their knowledge, and reshaping how education and heritage are shared.

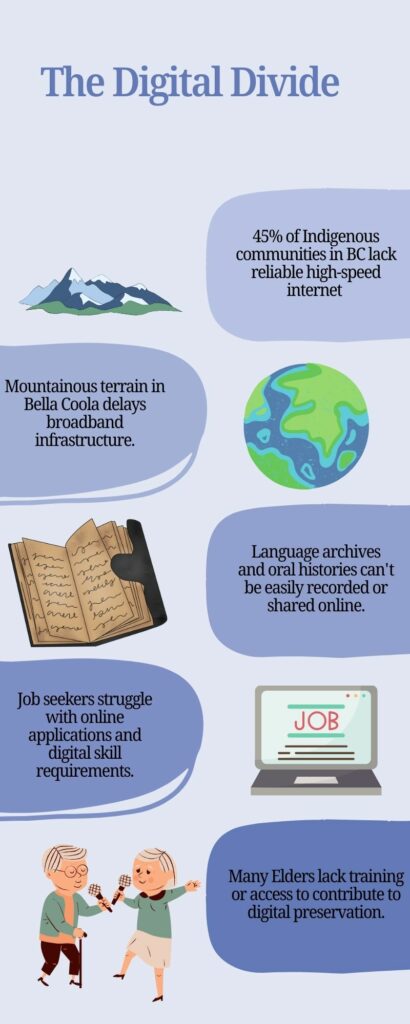

Reports from the First Nations Technology Council and platforms like FNIGC’s OCAP principles have also broadened my understanding. They make it clear that digital spaces must not be neutral zones they must be culturally safe and politically empowering. Internet access, as stated by the Technology Council, is not just a service it is an enabler of education, economic growth, language preservation, and cultural survival. Every Indigenous community that lacks access is left further behind.

This learning journey reinforced that the digital divide is more than technological it is emotional, cultural, and existential. Communities are fighting not just for Wi-Fi, but for the ability to speak their languages, tell their stories, and educate their youth in their own voices.

- Digital literacy must be culturally grounded and reflect Indigenous knowledge systems.

- First Peoples’ Map shows real examples of sovereignty over language, art, and territory.

- Data sovereignty includes who owns, stores, and controls Indigenous knowledge.

- Critical media literacy helps Indigenous youth challenge online stereotypes.

- Offline tools are used in rural areas where digital infrastructure is lacking.

- Intergenerational learning is supported by language apps and storytelling projects.

What I Learned

- The digital world can be a space for cultural safety, if it is designed inclusively.

- Infrastructure gaps are about more than access—they’re about identity and future.

- Indigenous communities have already built incredible tools; we need to amplify them.

What I Struggled With

- Finding resources that were truly Indigenous-led rather than institutional summaries.

- Grasping the depth of data governance and the politics behind storage and access.

What I Enjoyed

- Exploring the First Peoples’ Map and seeing digital cartography used for empowerment.

- Learning about language revitalization and the emotional importance behind it.

- Discovering Indigenous-led platforms like Digital Smudge that mix culture, tech, and care.

What started as a research project on digital literacy became a window into the spiritual, cultural, and political realities of Indigenous communities. These are not passive recipients of technology they are builders, creators, and leaders who are reshaping the digital landscape on their terms. The path forward requires not just access, but autonomy and we must all listen, learn, and support efforts that place Indigenous voices at the centre of every digital conversation.

Digital literacy, especially in an Indigenous context, extends well beyond the simple act of getting online. It involves questions of power, control, voice, and the preservation of cultural heritage. These values shape how information is collected, stored, and shared. It is the difference between a community being spoken about by outsiders and a community telling its own stories using its own words.

True digital sovereignty offers a framework for Indigenous peoples to design, guide, and define the technologies they use. This commitment requires everyone to listen, learn, and ultimately follow the leadership of Indigenous communities. Doing so means amplifying their innovations and honoring the data protocols that protect sensitive cultural information. It means recognizing Indigenous peoples as creators and builders whose work reshapes the digital landscape on their own terms.

The future of digital spaces rests on acknowledging the full spectrum of Indigenous knowledge systems and ensuring that digital literacy reflects a genuine respect for autonomy. This involves learning from those who have been systematically silenced and valuing their contributions as essential to all our futures. When Indigenous voices are placed at the core of digital development, the result is a richer, more equitable technological environment for everyone.